Home

HomeA letter arrives to the “partially recognised” country of Abkhazia. A friend writes a letter and waits. An answer arrives weeks later. Between fiction and documentation, the film “Letters to Max” by Eric Baudelaire presents a portrait of Abkhazia through an impossible conversations where every sentence and every word can be lost among borders and bureaucratic offices. But the communication is real, exists.

As part of the project, Baudelaire produced a book which collects every letter he exchanged with his friend in Abkhazia. A few weeks before the opening of ARTifariti 2016, when we were working in the film program which would be presented in the refugee camps of Tindouf (“Letters to Max” was one of the pieces we projected there), I bought the book through Lulu. I asked if sending it to the refugee camps in Algeria was possible, the address I wrote was: Escuela Saharaui de las Artes, Wilaya Boudoir, Saharaui Refugee Camp, Tindouf, 37000, Algeria. It was sent and I waited.

Process for Saray Pérez-Castilla’s project, Picture by Javier Andrada

While I was buying the book and finishing the last details before ARTifariti, a small advancement of the project was already there. My colleage the curator Charo Romero Donaire traveled to the camps three weeks before the opening with three artists: Jesús Palomino, Javier Andrada and Saray Pérez-Castilla. The last one was the only artist who had been in the refugee camps before, two years ago, recording the aural territory of Sahara desert, a long process of hard days driving to meet “deyars” (the oldest Saharawi, who still remember how was the life before the Moroccan invasion, when they were free nomads). Palomino and Andrada went there for their first time, some weeks before the event to study the context and develop their projects. The international participation of ARTifariti 2016 were necessarily organised through the tension of being there and being somewhere else, of living the context or just reading about it, of having the possibility of free movement inside the refugee camps or being immobilsed. We tried to remark on this opposition of positive and negative heterotopias as a key point to present the current situation of Western Sahara, and most of the artists answered dealing not with the borders, but with the movements and connections.

Installation with the books of “State of Siege”, Picture by Jesús Palomino

Jesús Palomino used his previous time to distribute a small edition of the poem Halat Hissar (State of Siege) by Mahmud Darwish, written during the siege of Ramallah (Palestine) in 2002. Darwish decided to stay in the city under the Israeli attack and to do what he can do: to write.

We do what prisoners do

we do what the jobless do

we sow hope

(State of Siege)

Palomino installed a shelving in a small library of the camps, a “social sculpture” to disseminate Darwish’s poem. The link between both contexts (Western Sahara and Palestine) creates a double meaning of connection and isolation, the enclosing of the siege offered a parallel situation with the permanent camps, but at the same time, the velocity of the books running among people and been exchanged offered the vision of places connected through a common language related with resistance.

Reading of “State of Siege” by Nacho Vilaplana

The project ended with a performance after a month and a half distributing the books. Palomino organised a public reading in a dark jaima (traditional Saharawi house). In the darkness of the desert the poem was revived again. But Mahmud’s words appeared previously like a virus in other context, a birthday party was the occasion for an spontaneous reading. It happened during a trip to Tifariti, a city in the Liberated Zone of Western Sahara (under Polisario Front control) bombed by Morocco in 1992. As part of ARTifariti, we did a trip to the Liberated Zone with a group of more than 50 artists and collaborators to visit the destroyed ruins of Tifariti, the prehistoric paintings of Erqueyez and the few soldiers who live there. Unfortunately, it started raining the evening before returning to the camps. The rain in the desert (certainly, a singular phenomenon) provokes a radical transformation in the landscape: the ground is not ready to absorb water, which produces the appearance of rivers and lakes in a couple of hours. This did not allow us to go back to the camps and we had to extend our staying 3 more days, till the ground dried.

Ruins in Tifariti

In the chaotic position of being caught up by the water and without communication, we had to reinvent the program of ARTifariti and adapt ourselves to this new situation. We projected the film by Eric Baudelaire in this context, on the wall of a small room in the shelter where we were sleeping. The film was watched just by a few of us and we had to stop it before the ending because of a power cut, but it was like Darwish’s words, a force showing how to resist in a critical situation where communication and words of love and friendship look imposible.

Projection of Eric Baudelaire, Picture by Charo Romero Donaire

The movements of words and letters, information, across frontiers has been taken by different artists as ways of talking about the enclosing space of refugee camps. A language which can break through walls is a necessity in the process of building constructive heterotopias. Against the enclosing spaces where every right is deleted, a heterotopia with the potential to create new worlds needs a permanent language exchange between the inside and the outside: narrations and fictions.

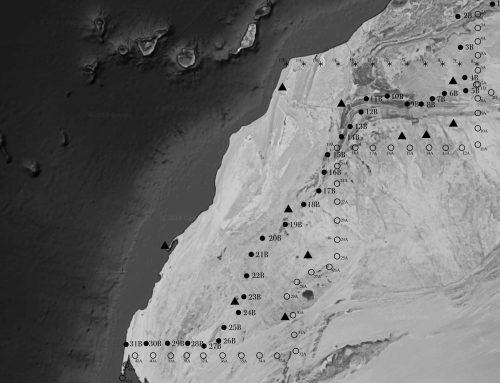

The books re-edited by Jesús Palomino, the collection of oral memories by Saray Pérez-Castilla or the letters sent by Eric Baudelaire are good examples of this flow of language, which can be also a metaphor of the global flow of capital and resources that supports the Moroccan occupation of Wester Sahara. The New Zealand artist Matthew Galloway has analysed the problem of the camps through the worldwide trade nets which connect Western Sahara with his house, in the port of Dunedin (New Zealand). He started to observed the ships arriving to his local port from Laayoune, in the occupied zone of Western Sahara, where the illegally extracted phosphates are loaded in large ships to fertilise grounds in other continents. Following this net of exchange, he found that the material used to fertile the rampant economy of his country was supported by the military occupation of an almost invisible land.

Flags from Matthew Galloway’s project, Picture by Matthew Galloway

He is developing a visual language with the combination of logos from some of the institutional characters envolved in the occupation: the Seal of Solom from the Moroccon flag, the olive branches from the logo of the United Nations, a raven from the logo of Ravensdown (a New Zeland fertiliser company) or the logo from the OCP (Moroccon phosphate company). With these elements Galloway has created designs, installations and a publication to be distributed as Palomino’s book and which he carried to the camps last November. A design combining the symbol of the United Nations and the raven from Ravensdown was also used in the poster of ARTifariti, a détournement from the original meaning to represent the complex agents and the fight of Western Sahara (the original raven was interpreted as a “bubisher” — swallow — in the camps, the bird that represent good luck in Saharawi tradition). This symbol was adopted and reproduced in banners, an spontaneus flag coming from the antipodes.

Banner with the image of ARTifariti 2016 during a conference by Mariantonia Hidalgo, Picture by Jose Iglesias Gª-Arenal

The seas are a place of movement and exchange, invisibility and flight, as well the digital sphere. The Saharawi fighting has been radically transformed after the emergence of social networks like Facebook or Youtube. The increase of smartphone among young Saharawis from the camps have helped them to have a public voice outside the official institutions, also to other minorities which have less presences and autonomy in the national discourse. Facebook has been a fundamental tool for the feminist Saharawi collective Desmaquillando Tabúes, they have used the platform to offer a different speech of liberation, linking feminism with national identity and defending a plural subject beyond traditional stereotypes. The group, based in Spain and Western Sahara, could not present their pictures and discourses by themselves during ARTifariti, but we could show a selection of images and we had a strong digital dialogue.

Display of photographs by Desmaquillando Tabúes during ARTifariti 2016

A connection between digital and physical worlds is a need in a situation of global precarity. The Spanish artist Maria Alcaide proposed to work in ARTifariti from her own situation as a worker without stability. Presenting herself as a “FREE WORKER”, she tried to connect with the young generation of Saharawis born as refugees in the camps; she used her own worker body to help people in different task as a way to find common points between a precarious situation in the European context and the extremly harder reality of the camps. One of the young people she worked for was Mohamed Sulaiman, a Saharawi artist and founder of the first independent art space in the refugee camps of Tindouf: MOTIF Art Studio. Alcaide’s visit to the camps was just the starting point of her project, still in progress; she is trying to find ways of work horizontally between the camps and Spain with her role of FREE WORKER (unpaid but able to cross borders) in the digital sphere.

Mohamed Sulaiman’s Facebook timeline

There are very different ways to broke the enclosing of the refugee camps but still keeping its potential characteristics. These practices have showed us how the extreme situation of the camps can be transformed and used to create different narratives which are not just the defence of an official national identity, but also an interesting tool in a global sphere. Neither the efforts of Desmaquillando Tabúes, nor the studies of Matthew Galloway or the poetic editions by Jesús Palomino refers only the Saharawi situation, but they observe a particular space to create a bigger discourse. There is global communication beyond capital globalisation, even when it looks impossible. When we left the refugee camps, the book by Eric Baudelaire I bought had not arrived yet and everybody thought it was lost between borders, but I received a call and a photograph two weeks ago: the book had found its ways to the Saharawi Art School.

Picture by Edi Escobar

Jose Iglesias Gª-Arenal

Jose Iglesias Gª-Arenal (Madrid, 1991) is a curator and artist based in London. He is currently studying the MA Curating the Contemporary (London Metropolitan University and Whitechapel Gallery, London) and he is part of the curatorial team of Artifariti 2016, International Art and Human Rights Meeting in Western Sahara. He runs the experimental editorial noPRESENT, focused on synergies among curatorial praxis, feminism and performativity.

http://www.joseiglesiasgarenal.com/

Featured image: Photogram from “Letters to Max”, Eric Baudelaire

One thought on “Where can we find our contemporary heterotopias? IV”